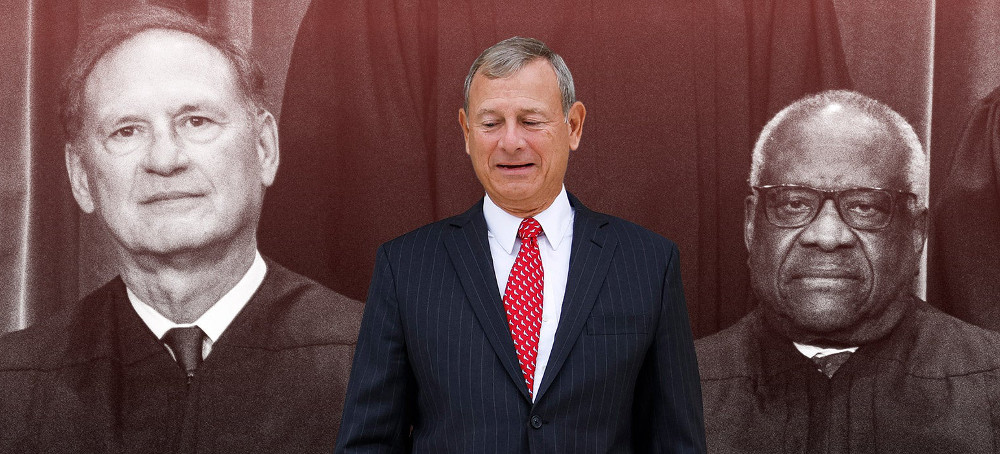

Trust the same justices who declined to follow the old rules to better adhere to the new ones? Good luck with that strategy. (photo: AFP)

Trust the same justices who declined to follow the old rules to better adhere to the new ones? Good luck with that strategy. (photo: AFP)

16 November 23

On Monday, the justices of the Supreme Court issued an extremely confusing statement laying forth the court’s brand-new ethics code for the justices themselves. These justices would like, through the announcement, to reassure us there is nothing actually “new” about the new code: “For the most part these rules and principles are not new,” the justices write. “The Court has long had the equivalent of common law ethics rules, that is, a body of rules derived from a variety of sources, including statutory provisions, the code that applies to other members of the federal judiciary, ethics advisory opinions issued by the Judicial Conference Committee on Codes of Conduct, and historic practice.” So what is “new,” then, is that the old rules are now binding on the justices?

No! Because of course the new/old rules are not precisely binding on the justices. That’s because the old rules, like the new ones, lack any sort of enforcement mechanism. So if the old rules were advisory principles, to which the old justices could look for guidance in deciding whether or not to adhere to them, so too the new rules, which are binding, will mainly serve as guidance to which the justices may newly look for guidance. Or, as the Associated Press plainly put it: “The code leaves compliance to the justices themselves and does not create any other means of enforcement.”

The most interesting question answered by the promulgation of the new/old rules, therefore, is who it was that was confused about the old rules to such an extent that they needed to be laid down. And as the court notes in its statement regarding the code of conduct:

The absence of a Code, however, has led in recent years to the misunderstanding that the Justices of this Court, unlike all other jurists in this country, regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules. To dispel this misunderstanding, we are issuing this Code, which largely represents a codification of principles that we have long regarded as governing our conduct.

In other words, it is not the justices who have misunderstood the various sources, canons, common law provisions, etc. when they failed to disclose gifts from donors with cases before the court, or when they attended Koch events that granted access to them for high-dollar donors, or even when they failed to recuse in cases in which they had an interest. The confusion, in reading the old rules, was evidently ours and ours alone. In order to dispel a public misunderstanding of the old rules— and why some members of the court declined to abide by them—the court is repromulgating virtually the same rules, which they themselves will enforce, but this time assuring us that we got it wrong the first time when we didn’t think they alone should enforce them. Trust the same justices who declined to follow the old rules to better adhere to the new ones, they urge. This time they really will unilaterally and in secret make better choices. Then and only then will your confusion desist.

Because there is no mechanism by which rule-breaking can be investigated, or adjudicated, the new code serves largely as what one can only describe as a compendium of old whines in new bottles. Come for the whining about bodily attacks on jurists, stay for the whining about how they need book revenue. If all of this material sounds extremely familiar, that’s because the substance of it is all stuff other judges have been doing for years, as the justices have continued to explain on repeat why they can only try to be bound by as much of it as they choose.

The new code further commits to “uphold the integrity and independence of the judiciary” and to “avoid impropriety and the appearance of impropriety in all activities.” This is of course the lodestar of the old rules and of an April statement in which the justices collected all these old rules as part of an old, new pledge to“reaffirm and restate” their commitment to said rules. Surely yet to come will be the graphic novel version of the old rules, the Netflix version, and the collectors’ edition action figurines, each of which will affirm that the rules—once confusing to the public but always crystal clear to the justices—are now crystal clear to everyone, even if still left entirely to the justices’ discretion to enforce on their own, without oversight or actual enforcement powers.

What’s also clear from the new/old rules: The “appearance of impropriety,” a test that has to do with how we the public define impropriety, is also being, once again, left entirely to the court to determine and uphold. In the event that a future justice fails to, say, repay a loan on a recreational vehicle, or says that he took an open seat on a private jet because nobody was using it, we can all rest assured that the impropriety therein is our own. And the tone throughout—the patient parental explanation that this is our stupidity in forcing this issue—is deeply worrisome coming from a chief justice who refused to testify on these very matters last spring and a justice who has said in a newspaper interview that Congress has absolutely no role to play in regulating the court.

Finally, there are lots of places in the new/old code where you will find sections that appear to have been reverse-engineered to paper over the misconduct that we have learned of this year with caveats about “knowingly” and “now in effect.” Old failures to disclose? Bygones. There is a lengthy explanation of why the need to have nine justices on most cases, “the rule of necessity,” will trump the need for an individual recusal. There is language that attempts to clean up judicial participation at political events and Federalist Society dinners, use of staff for judicial book sales, and some financial disclosure loopholes, but the tell, again, is that on these matters, the justices believe the confusion has been yours; they have been perfectly consistent all along.

If there is a lesson, still, to be learned from the ethical revelations of the past year, and the ethics industrial complex that journalism has erected to continue to mine the infractions, it is that newsgathering matters—that when the justices are left to their own ethical devices, misconduct happens, it goes ignored by the other justices, and it becomes weaponized by wealthy entities seeking to alter outcomes in cases, such that an entire infrastructure of corruption goes undetected for years. Being granted a peek into the tent in which judicial monarchists nod sagely and pinkie swear they are still adhering to the rules they ignored does little to assuage a public that still wants to know how Leonard Leo seated three justices and made a ton of bank on a project predicated in ignoring ethical rules.

On Monday, after immense pressure from the public, journalists, good-government groups, and Congress, the court’s answer seems to chiefly be that this is annoying. And that if they explain again that they are following the old rules, we can all go back to the days of undisclosed luxury salmon fishing and big donor meet-and-greets at the Supreme Court historical society and Koch junkets. This entire document reads like a great big “it’s not me, it’s you” to a public that continues to understand that we the public are not, in fact, the primary ethics failing of the Supreme Court.

Props to the justices for signing onto a thing, even if it’s an old thing recast as a new thing, principally drafted with the intention of instructing us that they still can’t be made to do anything. It was probably difficult to get some of the court’s present membership to concede even that the public is hopelessly confused and needs a tune-up. My guess is that this unenforceable new set of old rules will mollify close to nobody. But insofar as it’s phrased to imply, perhaps for the first time since this ethics mess began, that the court is aware of public opinion, it’s a tiptoe in the right direction. Maybe the fact that the court is finally willing to admit that there’s a problem—even while insisting it’s the public with the problem—signals that this is a conversation and not a sermon from the mount. And maybe that’s the best start we can hope for.

Coke Can Clarence's wife Ginni Thomas is laughing at the new code all the way to the bank.

No comments:

Post a Comment