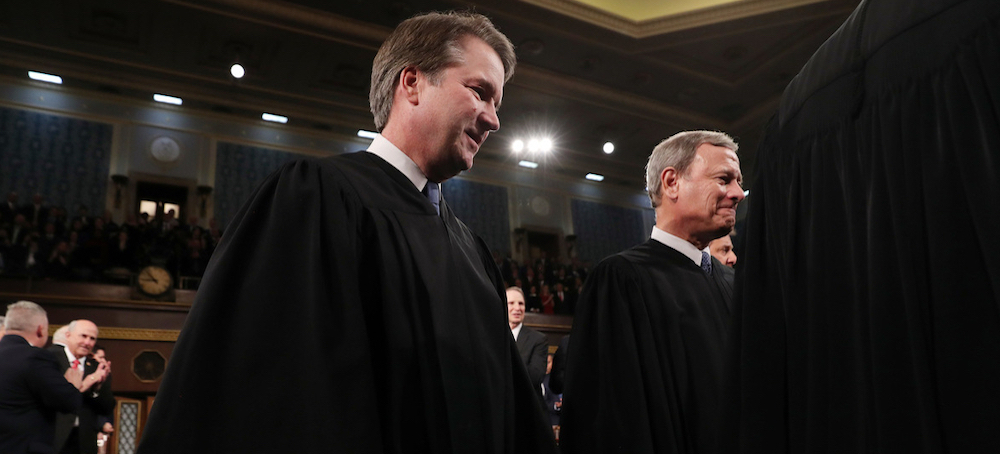

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

At the top of Page One of Chief Justice John Roberts’ “Year End Report on the Federal Judiciary” is a photograph of a courthouse—the J. Waties Waring Judicial Center in Charleston, South Carolina. The picture is part of Roberts’ effort to claim the stories of heroic judges who battled Jim Crow in the civil rights era as allegories for judges facing legitimate critiques today. Modern jurists whose extreme decisions draw public rebuke, the chief justice implied, face the same misbegotten or even “illegitimate” backlash as the brave men and women who used their judicial authority to dismantle American apartheid.

On this week’s episode of Amicus, Dahlia Lithwick was joined by 14th Amendment scholar and storied civil rights litigator Sherrilyn Ifill to discuss why some members of the federal judiciary are so fond of using this civil rights–champion cloaking mechanism to rebuff criticism of their rulings. An excerpt of their conversation, below, has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Dahlia Lithwick: I wanted to talk about this cynical use of the history of the Civil Rights Movement to co-opt the notion that the current justices are very much like the brave judges who stood alone in the civil rights era and suffered the consequences.

We already saw this back in November when Judge Edith Jones used a Federalist Society panel to attack law professor Steve Vladeck, while placing criticism of current Ken Paxton fave Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk on a weird level playing field with civil rights–era Judge William Wayne Justice. And now we have the chief justice of the United States embracing the same notion.

Sherrilyn Ifill: It angers me, obviously, but I also often get a chuckle out of it. Because so much of what we are seeing in our profession and among conservative judges and litigators is this traumatic response to the heroism of the Civil Rights Movement and the work of civil rights lawyers and the work of the judges deciding civil rights cases. There’s a traumatic response that has resulted in this effort to cloak themselves with the heroism of that period—to suggest there is something equal about what they are doing and the courageous efforts of those who worked through huge challenges trying to make this country a true democracy during the Civil Rights Movement. It makes me chuckle because the trauma is so evident, but it also makes me angry because it is fundamentally ahistorical and untrue.

In his year-end report, Chief Justice Roberts cites to Judge Julius Waties Waring and then he cites to Chief Justice Earl Warren, both of whom received threats of violence against them for their civil rights decisions. I found myself deeply offended, particularly by the Waties Waring comparison. Julius Waties Waring was the scion of an old Charleston family who became a federal judge. As civil rights cases came before him, he set upon a path of trying to learn about the history of race in this country. He and his wife would read together every night. They would question each other. He was being exposed to a world he had never known. He lived in the most attractive house on the main street of Charleston and was a fixture of Charleston society.

As he started to read and learn, he was also doing what judges are supposed to do in litigation, which is learn from litigation, as more and more cases come before them. He issued decisions in a number of cases that were among the most important of the civil rights cases, including his dissent in the Briggs v. Elliott case, which was the South Carolina Brown v. Board case. The court ruled against the plaintiffs, and against Thurgood Marshall in that case, but Judge Waties Waring’s dissent became the template for what became the majority decision in Brown v. Board of Education. As a result of his civil rights decisions, Waties Waring was subject to violent attack—a bomb was thrown at his house one evening as he was home with his wife. But he was also ostracized by the society that he had been a part of.

I emphasize this because it wasn’t just that there were violent threats by racists; it was also that the society of people, of which he was a part—upper class Charleston society, his colleagues within the judiciary and so forth—ostracized him and his wife. They were socially dead. And as a result, he and his wife moved from Charleston, South Carolina, to New York, where he lived out the rest of his life. He never returned until he was buried.

I spoke at the dedication of the courthouse to Waties Waring when the name was changed. It had been named after Ernest Hollings, the senator from South Carolina, and with Sen. Hollings’ consent, it was renamed to honor Waties Waring. A picture of that courthouse is included in the chief justice’s year-end report. This comes after Judge Edith Jones compared Kacsmaryk to Judge William Wayne Justice on that Federalist Society panel in November. Professor Vladeck had written about the one judge district in Texas where conservative lawyers are filing their cases so they can appear before Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk, and Judge Jones said, with triumph in her voice, “What about Judge Justice?” Civil rights litigants would try to appear before Judge Justice during the 1960s and 1970s; he was appointed by President Johnson and he’s considered a champion by civil rights litigators.

It’s no comparison to Matthew Kacsmaryk. First of all, the cases that were filed before Judge Justice were filed in a district that was associated with the very claims that were being made. It wasn’t just civil rights attorneys from all over the country with claims that were not connected to Texas filing their cases in Texas. That’s what’s happening with Kacsmaryk.

The larger point about those civil rights–era judges, who we now think of as champions, is that they were in the small minority. Most of the other judges were abusing the system. When Thurgood Marshall first appeared before Judge Waties Waring, he said it was the first time he had ever been able to truly try his case, that he had been able to put on all his evidence, that the judge actually listened to him and didn’t run over him. Thurgood Marshall said he was astonished that Judge Waties Waring allowed him to litigate his case.

So it wasn’t that somehow civil rights litigators were manipulating the system to appear before these judges to guarantee a win; it was that so many of the other Southern judges would not give a fair hearing to civil rights claimants. Think of the judges who turned their back on Constance Baker Motley, or who wouldn’t say her name—those were the other judges in those districts.

So for Chief Justice Roberts to make the comparison between criticism of our current judiciary and what was faced by those civil rights–era judges in his year-end report—it’s unfair, it’s a distortion of that history, and it’s once again an attempt to cloak oneself in the history of the Civil Rights Movement.

Of course, the worst example of this is Justice Samuel Alito saying that basically Dobbs overturning Roe is like Brown overturning Plessy. You can’t just snatch from this history the snippets that you want to make your point and suggest that they are equivalent, because they are not, and there are important differences that actually speak to our system.

Our system is not always fair. It was not fair. And we have to be able to speak to that. Constance Baker Motley described Judge William Harold Cox as the most racist judge who ever sat on the federal bench. She wrote that recollection of litigating before him in her memoir, by which time she was a federal judge. Was she not supposed to speak? This idea that critiquing the judicial system or judicial opinions is itself corrosive of the rule of law is a kind of through-the-looking-glass, bizarro-world conception of how lawyers are supposed to engage with the justice system.

No comments:

Post a Comment