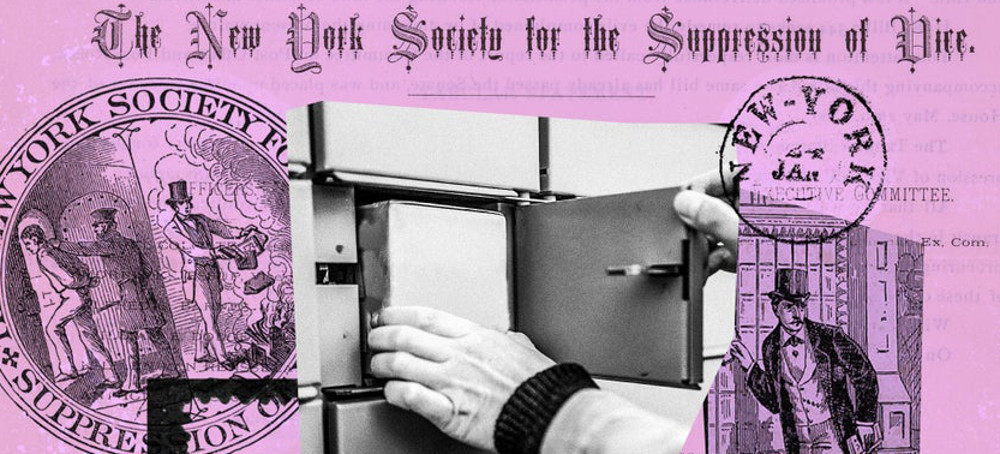

Photo illustration by Slate. (photo: Library of Congress)

Photo illustration by Slate. (photo: Library of Congress)

If you thought overturning Roe was bad …Jill Filipovic Slate

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, just months shy of the landmark abortion case’s 50th birthday, millions of Americans were stunned that the highest court in the land had just set our rights back half a century.

What we didn’t realize: Half a century is nothing. Less than two years after Roe fell, the conservative movement is taking women back not just 50 years. It’s rewinding the clock more than 150 years.

Case in point: Arizona’s abortion law, which is now in place statewide and which was passed 160 years ago, in 1864—when the Civil War was raging, before nearly a third of what are now the 50 U.S. states formally existed, and when women didn’t have the right to vote. Arizona itself wouldn’t be admitted to the Union for almost another half-century, having been recognized as an American territory only the year before.

That archaic 1864 law makes nearly all abortions a felony and threatens to lock up any abortion provider for a term of two to five years. The day after the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that this archaic law could go into effect, Arizona Democrats tried to repeal it. Arizona Republicans in both legislative chambers blocked those repeal efforts, while Arizona anti-abortion advocates have fought to keep abortion rights off the ballot.

When the 1864 abortion law was passed, the territory’s Legislature was led by a pedophile who married, then divorced and sometimes impregnated (in and out of marriage), a series of children, girls who today would be in middle and early high school and largely too young to get their driver’s licenses, according to reporting from the Washington Post’s Monica Hesse. This was legal because, across the U.S., parents were allowed to marry off their young daughters, and the age of sexual consent was largely prepubescent, typically at 10 or 12. In Delaware, it was 7. The same document outlawing abortion in Arizona also outlawed interracial marriage and allowed for the indentured servitude of Native American children. There’s a whole section on electric telegraphs.

All of these laws were written by men. When Arizona passed its abortion law, not a single woman had yet been elected to any state legislature anywhere in the nation, and women would not hold any such role for several more decades. This was an era in which women were largely under the control of their husbands, and they generally had little right to possess property, control their own wages, and even lay claim to their own children. Black women were often still literal property. Courts in several U.S. states spent the better part of the 19th century ruling that husbands were legally entitled to beat their wives.

The Arizona abortion ban followed centuries in which abortion was treated mainly as a woman’s concern, and was permitted until “quickening,” or the moment a pregnant woman could feel the fetus start to move. (This was also the Catholic Church’s position for hundreds of years, by the way.) But by the mid-19th century, women were gaining unprecedented rights and freedoms. This did not sit well with the patriarchal and the powerful, including the all-white-male American Medical Association, which had just formed in 1847. Reproductive health care was largely the purview of midwives and other female practitioners, posing a problem for the male doctors who wanted a monopoly on the profession. The leader of the anti-abortion crusade, physician Horatio Robinson Storer, wrote, “Medical men are the physical guardians of women and their offspring” and, as such, have a duty to criminalize abortion. He lamented that birthrates were decreasing, with foreigners (Catholics especially) outbreeding white Protestants; asserted that women, who didn’t even seem to feel guilty about abortions, must pay a serious criminal price; and believed that women who were getting pregnant too frequently had only themselves to blame and were often those who chose to “forego the duty and privilege of nursing, a law entailed upon them by nature, and seldom neglected without disastrous results.”

According to Storer, who wrote to legislatures across the nation urging them to outlaw abortion, a woman’s “holiest duty” was “to bring forth living children,” a responsibility that was routinely interrupted by “female physicians and midwives” (emphasis his), who claimed expertise “in rivalry of the male physician” and whose work Storer opposed, alongside anything else outside a woman’s “proper and God-given sphere.” As for claims that women sought terminations because nonstop pregnancies were difficult and dangerous, or because they could not afford or did not want additional children, he objected to such arguments “which would justify abortion as necessary for the mother’s own good” as “a selfish plea.”

Storer lauded the Catholic Church’s position that a fetus was of greater import than a pregnant woman, and he admired the insistence on saving a fetus’s life even if it meant that the woman died. He eventually converted to Catholicism, in large part because of the church’s position on abortion.

Almost a decade after Arizona’s abortion ban, and as physicians including Storer were making sure similar bans were put into place across the U.S., Congress passed the Comstock Act—that was in 1873, exactly 100 years before the Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade and legalized abortion nationwide. The Comstock laws prohibited the mailing of “obscene” materials, including contraceptives, abortion-inducing drugs or devices, sex toys, and anything the most extreme prudes of the era might deem pornographic. (The architects and supporters of this legislation did indeed try to forbid, in their words, “every filthy book, pamphlet, picture, paper, letter, writing, print, or other publication of an indecent character,” which at one point included even anatomy textbooks.) Anthony Comstock, the chief prude for whom the act is named, was an enthusiastic book-banner and suffragist-opposer.

The Comstock Act is back now too: It’s one of the laws the anti-abortion movement is hoping to use to ban the abortion-inducing drug mifepristone. Leaders of the anti-abortion movement have been exceedingly clear that they plan to try to revive the Comstock Act in order to ban abortion nationwide, and possibly contraception as well.

It’s not a coincidence that the early anti-abortion movement in the U.S. was one headed by men, in reaction to expanding rights, freedom, and power for women—just as it is not a coincidence that today’s anti-abortion movement, formed in opposition to rapid gains in women’s rights during the 1960s and ’70s, has seen its most significant victory thanks to the most overtly misogynistic president in modern American history, a serial philanderer, a many-times-accused sexual harasser and assailant, a man recently found liable for sexual abuse.

The history of these laws tells us quite a bit about our present, especially what motivates the most aggressive abortion opponents. Attempts to criminalize abortion have always gone hand in hand with conservative and religious views on gender roles, with abortion bans functioning as blunt instruments that force women back into our God-given place as dutiful mothers and obedient wives. And it’s equally impossible to separate out efforts to legalize abortion from broader moves toward gender equality, both in the liberalization of abortion laws—efforts led by feminists around the world—and in the feminist outcome of those liberalized laws. That would be record progress for women and girls, from more egalitarian interpersonal relationships to greater financial power to skyrocketing educational and professional achievements to much longer and healthier lives for women and the children we bear.

Those in the anti-abortion movement are relying on the letter of the law from 150 years ago not simply because it’s convenient. They’re leaning on century-old laws because they want to make America a certain way again, and those century-old laws both sprang from and enabled a particular kind of society. Those laws existed only because women were legally, socially, and economically second-class citizens, their rights and liberties determined by white men who enjoyed exclusive control over every lever of political power. And those laws had the effect of maintaining that same complete male domination—that is, until generations of feminists dismantled them and put a great many cracks in the system that created them.

And this, still, is the fundamental divide. Should women’s rights in America go back to what they were in 1873? Feminists have spent the past 150 years painstakingly chipping away at the laws that forced our subservience. But today’s anti-abortion movement, and its representatives in the Republican Party, has a different answer, one it makes clear every time it argues that women’s bodies should be regulated by laws that existed before any woman had a legal say in them.

RBG made her mark and women made theirs - but then a few male Arizona judges said, "Not so fast, sweeties."

No comments:

Post a Comment